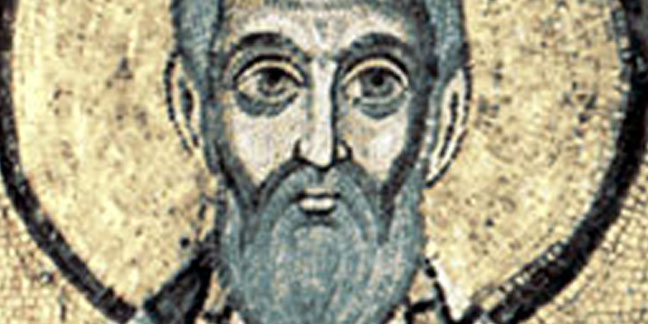

On May 12 the Church honors St. Epiphanius of Salamis, an early monk, bishop and Church Father known for his extensive learning and defense of Catholic teachings in the fourth century.

On May 12 the Church honors St. Epiphanius of Salamis, an early monk, bishop and Church Father known for his extensive learning and defense of Catholic teachings in the fourth century.

During a 2007 visit with the Orthodox Archbishop of Cyprus, Pope Benedict XVI praised Epiphanius as "a good pastor" who "pointed out to the flock entrusted to him by Christ, the truth in which to believe, the way to take and the pitfalls to avoid."

"At the beginning of this third millennium," the pope reflected during the visit, "the Church finds herself facing challenges and problems not at all unlike those which Bishop Epiphanius had to tackle."

Epiphanius was born in Palestine around 310 or 315, the son of Greek-speaking Jewish parents. He is said to have been drawn to the Church after seeing a monk give away his clothing to a person in need. Not long after his conversion, he became a monk himself, spending time in the Egyptian deserts.

Around 333 he returned to the Holy Land and built a monastery near his birthplace in Judea. Epiphanius showed great dedication to the rigors of monasticism, which some of his contemporaries considered excessive, although he insisted he was only seeking to work faithfully for God's kingdom.

The devoted monk was also a man of extraordinary learning, versed in the Hebrew, Egyptian, Syrian, Greek and Latin languages and literature. For more than two decades, until 356, Epiphanius was a disciple and close companion of St. Hilarion the Great, a monk known for his wisdom and miracles.

The spiritual bond between them remained unbroken after Hilarion left Palestine around 356. Hilarion's influence within the Church of Salamis, in present-day Cyprus, led to its choice of Epiphanius as bishop in 367.

During his years in Palestine, Epiphanius had frequently offered guidance and help in the Church's struggle against Arianism, the heresy which denied Jesus' eternal existence as God. As a bishop, he went on to write several works arguing for orthodox teaching on subjects like the Trinity and the Resurrection. He became known as the "Oracle of Palestine."

Determined to protect the Church from error, Epiphanius became involved in various controversies and was known as a strong voice for orthodoxy. In some instances, however, his zeal was misguided or uninformed, as when he inadvertently became involved in a plot against St. John Chrysostom.

Likewise, some of Epiphanius' apologetic works are regarded today as inaccurate or flawed on certain points. Nonetheless, he is revered among the early Church Fathers, and his writings – which contain important formulations of orthodox belief – are cited in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

St. Epiphanius of Salamis died in 403, while returning from Constantinople after distancing himself from the attempt to depose St. John Chrysostom. Sensing the approach of death, he gave his disciples two final pieces of advice: to keep God's commandments, and guard their thoughts against temptation.

He was buried on May 12, after his ship's return to Salamis. The Seventh Ecumenical Council, in 787, confirmed his reputation as a Church Father worthy of veneration.

— Benjamin Mann, Catholic News Agency

Matthias, whose name means “gift of God,” was the disciple chosen to replace Judas as one of the 12 Apostles. The Acts of the Apostles states that he was also one of the 72 disciples that the Lord Jesus sent out to preach the Good News.

Matthias, whose name means “gift of God,” was the disciple chosen to replace Judas as one of the 12 Apostles. The Acts of the Apostles states that he was also one of the 72 disciples that the Lord Jesus sent out to preach the Good News.

Matthias had followed Jesus since His baptism and was a witness to His Resurrection and His Ascension, according to St. Peter in Acts.

According to Acts 1:15-26, during the days after the Ascension, St. Peter stood up in the midst of the brothers – about 120 of Jesus’ followers. Now that Judas had betrayed his ministry, it was necessary, St. Peter said, to fulfill the scriptural recommendation that another should take his office. But all of the apostles had been chosen by Jesus Himself, so the group of His followers needed to determine how to choose among them.

St. Peter then proposed the way to make the choice. He had one criterion: that, like Andrew, James, John and himself, the new apostle be someone who had been a disciple from the very beginning, from His baptism by John until the Ascension. The reason for this was simple – the new apostle must become a witness to Jesus’ resurrection. He must have followed Jesus before anyone knew Him, stayed with Him when He made enemies, and believed in Him when He spoke of the cross and of eating His Body – teachings that had made others melt away. “Therefore, it is necessary that one of the men who accompanied us the whole time the Lord Jesus came and went among us, beginning from the baptism of John until the day on which He was taken up from us, become with us a witness to His resurrection” (Acts 1:21-22).

The group of Jesus’ followers then nominated two men who fit this description: Joseph Barsabbas and Matthias. They prayed and then drew lots. The choice fell upon Matthias, who was added to the Eleven.

Matthias is not mentioned by name anywhere else in the New Testament.

According to various traditions, he preached in Cappadocia, Jerusalem, the shores of the Caspian Sea (in modern-day Georgia) and Ethiopia. He is said to have met his death by crucifixion in Colchis or by stoning in Jerusalem.

There is evidence cited in some of the early Church fathers that there was a Gospel according to Matthias in circulation, but it has since been lost, and was declared apocryphal by Pope Gelasius.

He is invoked for assistance against alcoholism, and for support by recovered alcoholics.

— Catholic News Agency, Franciscan Media, Catholic Online